Raymond Baltar, SEC’s Biochar Program Manager.

Sonoma Ecology Center has for many years been a leader in the movement locally and throughout California to expand the production and use of biochar. Biochar, a specially made form of charcoal that is suitable for use in agriculture and that is created from surplus woody materials and crop residues, has been shown to reduce water usage, contribute to sustainable agriculture practices, and sequester carbon for long periods in soil. Today, we sat down with Raymond Baltar, SEC’s Biochar Program Manager, to better understand how biochar is produced and used in our region and beyond, and what the potential is for more widespread biochar usage.

Closeup of a branch that has been turned into biochar. Photo courtesy of Raymond Baltar.

When we’re talking about biochar production, there is some concern that biochar’s production can undercut efforts to sustainably manage forests. Can you tell us about what we, SEC, and other organizations do to create biochar?

The main feedstock that we use to create biochar comes from surplus forestry materials. Often called “wood waste” these underutilized bioresources mostly come from either public or private fuels reduction projects. To reduce fire danger SEC and other organizations perform shaded fuel breaks and other thinning projects which reduce the amount of vegetation in order to better contain fires should they break out. There are estimated to be about 1 million tons of these low-value, unmerchantable slash materials produced in California annually, some of which could (and we believe should) be converted to biochar.

There are certain countries that do grow renewable crops like bamboo to make biochar, which grows very quickly and is considered a renewable crop. But here in the Western U.S., we only advocate using the massive amount of surplus bioresources, much of which is simply burned rather than upcycled into a valuable soil amendment like biochar.

Sonoma Ecology Center staff performing fuel management work at Montini Open Space Preserve this Spring. We cut dead, downed, and dense vegetation along trails to effectively create a “shaded fuel break,” which can help slow the speed and intensity of a fire if it moves through a landscape. Excess vegetation from projects like these can be used to create biochar.

So, we’re only using the surplus material that is gathered during activities which improve the forest and reduce fire danger. There are those who will say, ‘just leave the forests alone.’ But we can’t do that anymore in areas like the WUI (Wildland Urban Interface) because we have moved our communities into the forest. And in order to protect the people that live in these areas we need to manage these forests. Also, in the West forests used to be burned regularly by indigenous cultures for thousands of years, in order to reduce the amount of the excess material that can cause conflagrations like we’ve had in 2017, 2019, and 2020. A lot of that was caused by forests that were way too dense because we have tried to remove fire from the landscape. So there’s a big move right now in California and elsewhere to do what are called prescribed fires—large-scale broadcast burns—that had been done for centuries by indigenous people to help reduce uncontrolled fire risk, to improve habitat for game, for pest control, and to improve biodiversity. SEC has conducted some of these burns on local private lands, and these involve purposely lighting fires under controlled conditions to reduce ladder fuels, invasive species, and small diameter trees to help prevent much more serious fires.

A prescribed burn SEC conducted at Van Hoosear Wildflower Preserve in 2020 that reduces uncontrolled fire risks.

What do most farmers and landowners generally do to deal with surplus, or leftover vegetation waste when they don’t participate in creating biochar?

There’s generally two things they do with it. There’s standard open burn piles. You can burn surplus biomass according to the regulations of the local air districts.

For example, in our region, there are plenty of vineyards. After 20 to 30 years, or even shorter time periods if certain varietals come in or go out of fashion, vineyard managers pull vines and replant which creates huge piles of vines. Until fairly recently, vineyard managers would just burn these materials and I’m sure you’ve seen the smoky plumes that often come with these burns during winter months.

SEC putting out a conservation burn pile at a vineyard in Monterey County. This method of creating biochar creates less emissions than the standard open burn pile. Photo courtesy of Raymond Baltar.

A second method of processing these vines involves chipping, which is more costly but considered preferable to traditional open burning. Chipping involves feeding surplus wood materials through a diesel-powered machine that processes it into wood chips that can be used for children’s playgrounds or landscaping. While chipping produces a useful product, chips degrade over time and much of the CO2 that they contain is returned to the atmosphere. Chippers also require fossil fuels to power them. When you produce biochar, it suspends a portion of the CO2 as a very stable, recalcitrant form of carbon, which also has multiple benefits for building soil health. And that is why producing biochar is so important, because it’s a form of carbon sequestration and is considered a “natural climate solution” by groups like the United Nations’ IPCC and The Nature Conservancy.

What are some of the ways that biochar can be made?

In general, although biochar can be produced using manures, corn stover, rice straw, and even dried sewage sludge, up until now it has primarily been made from forestry materials because wood is denser with the potential to produce more biochar. There are two main industrial processes used to make biochar: pyrolysis and gasification. Pyrolysis heats (or bakes) biomass at high temperature in low-oxygen environments and produces several usable byproducts as well as biochar. Gasification uses even higher temperatures to convert biomass into gases that can be used to produce energy, also with biochar as a byproduct. Most of the biochar produced in California currently comes from large-scale Co-gen facilities. Biochar can also be made using low-cost kilns that are available commercially, or even by using an alternative burn pile technique called the Conservation Burn. We teach both of these methods in local field training events. As mentioned, in our neck of the woods we only use surplus material that is generated through ecological forestry activities.

SEC producing biochar through the flame cap kiln (left) and the conservation burn pile (right) during our emissions testing study. The study aims to measure greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) and Particulate Matter (PM) 2.5 emissions from various burning techniques.

What kinds of benefits can we expect from biochar production?

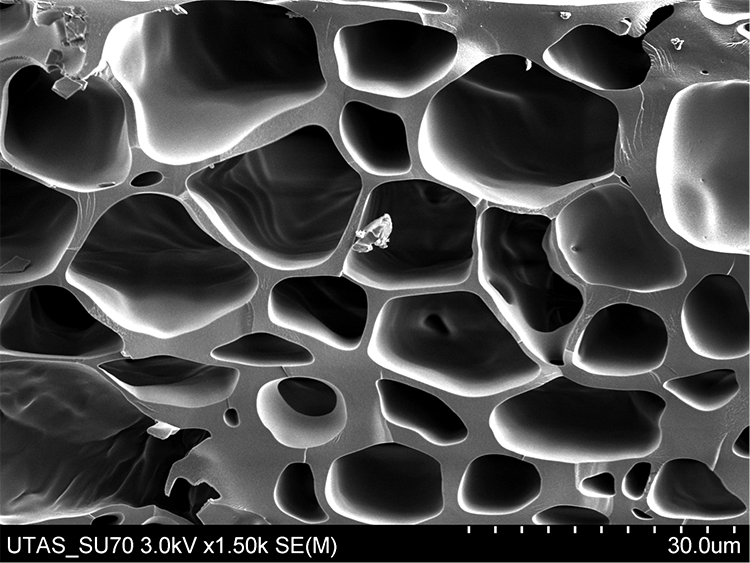

A lot of the vineyards are trying to be as sustainable as possible. Using biochar that was made from one’s own surplus bioresources is a more sustainable practice than traditional pile burning and can enhance soil health, particularly in areas with low soil organic matter. And, biochar can reduce water and nutrient use, especially in sandy soils. You know, during the recent extended drought years, water efficiency was a critical concern to a lot of farmers, and biochar does save water because of its porous structure. There are millions of tiny little holes in biochar—it is absorbent. And we like to say it is a condo for microorganisms. Mycorrhizal fungi that contribute to soil health also have a unique, symbiotic relationship with biochar. Think of biochar not as a fertilizer but as a storage device — when you put it in soil it holds water and nutrients and slowly releases these things over time to feed the roots of plants.

Biochar as seen through a microscope. Its porous structure helps improve water retention in the soil. Biochar is able to release water and nutrients slowly over time, which can help farmers conserve water and foresters improve tree survival rates.

Biochar has been shown to be particularly beneficial when planting trees to reduce mortality because those trees continue to get water in stressful times. That’s one of the reasons we were recently awarded two CAL FIRE Green Schoolyards Planning Grants where we will be planting many shade trees in 12 elementary schools and using biochar to save water and nutrients over time. These projects will also allow us to teach the kids about biochar and soil health as part of the educational component of the grants.

As mentioned, when commercial systems are used to make biochar (pyrolysis and gasification) numerous byproducts can be captured and utilized such as process heat, syngas, and in some cases bio oil. Heat and syngas can be used to produce renewable energy, and the bio oils can be used as a source of chemicals used by certain industries. The bio-oils can also be used by agriculture.

Do you see a lot of interests in biochar? What role does SEC play in advancing the production of biochar locally or state-wide?

We have been the main educational source and promoter for biochar in California since 2009. We’re also very plugged into the national network of scientists, educators and producers.

SEC has done over 50 presentations and field trainings since 2013 on low-tech biochar production in Sonoma County and around the State. Often done in collaboration with RCD’s, progressive wineries and farms, and both large and small private landowners, these events can draw up to 40 people interested in alternatives to traditional open burning that also produce a valuable soil amendment that can be used right back on their property.

An outreach event regarding biochar that SEC organized at a Mendocino County reservation in 2016. Photo courtesy of Raymond Baltar.

I learned at the recent National Biochar Conference that there are now over 30,000 studies from around the world, including a number of meta-analyses, that have shown, overall, various benefits of biochar use as a soil amendment.

SEC has conducted several biochar field trials with other partners including a 5-year study at a vineyard in Monterey County funded by the California Department of Water Resources and in collaboration with UC Riverside, Pacific Biochar, and Monterey Pacific Vineyard Management. This trial showed that Monterey Pacific could significantly increase production by using biochar and compost added to the vine row during planting, and using the same amount of water as the control rows. The most current results from Year 5 of that study are available here. While not every vineyard will duplicate these results, they are promising enough to be attracting a lot of attention in the grape growing community and we have been working to get the word out.

Grapes were collected from a 5-year field trial at the Oasis Vineyard Monterey County. This study was managed by Sonoma Ecology Center and funded by the California Department of Water Resources.

Biochar has really only taken off in the last few years, and we have spent a lot of time and effort to educate farmers and other key decision makers. To invest in biochar, farmers have to have a reasonable assurance its use will pay off and that adding biochar will not, in the case of vineyards, affect grape quality. We have some of that data now, and it comes from one of the most scientifically rigorous studies done thus far in the State. But there are many variables to studies like this and we need to build on this research, so we are looking for additional opportunities for follow-on field trials—especially here in Sonoma County.

What are some challenges for individuals or businesses and farms trying to access biochar?

Bags of high quality biochar or biochar blends that you can purchase in garden centers or building supply haven’t been widely available, and it has been fairly expensive. But that’s changed a lot just in the last few years and you can now find bags of biochar in certain knowledgeable garden centers like Harmony Supply in Sebastopol or “grow” stores catering to the cannabis community. Cubic yard quantities can be purchased from West Marin Compost, and the truckload quantities needed for larger farming applications can be sourced from companies like Pacific Biochar at significantly cheaper prices than just a few years ago. SEC teaches people how to make biochar on a smaller scale, and landowners with surplus woody materials who want to experiment with it can hire our team to train them how using specialized, portable kilns, or through the use of a technique called a conservation burn.

Biochar and chicken manure pellets produced by a farmer in Petaluma that SEC worked with. Photo courtesy of Raymond Baltar.

Why is supporting regional, local sources of biochar important? How is this different from our current system of getting and using soil amendments?

We do need to have localized, community-sized production facilities as it isn’t economic to ship biomass or biochar long distances. Shipping is expensive and can adversely affect biochar’s positive greenhouse gases (GHG) savings potential. In general you don’t want to move biomass more than 25 to 35 miles before processing or reaching its end use, and shipping biochar long distances can cost more than the biochar itself.

You should think of biochar not as a singular product but as a material that can have a wide range of characteristics and effects depending on the type of feedstock used, the process used to make it including the temperature and residence time, how it is post-processed and “inoculated” with nutrients prior to use, what type of soil it is used in and what type of plants are grown. Regarding inoculation, in most cases if you are using biochar to enhance agricultural production it should first be blended with a good quality compost, compost tea, or some other nutrient source. Biochar is not a fertilizer replacement but should be thought of as a nutrient and water delivery system able to feed plant roots over time.

SEC Restoration Crew working with a landowner in Petaluma to demonstrate the flame cap kiln in producing biochar. Photo courtesy of Raymond Baltar.

Studies have shown that if you add compost to grazing land it builds up the soil organic carbon and soil organic matter significantly as well as increase soil moisture. Biochar, if blended with compost, could enhance these effects and increase soil water retention even more—especially in sandy soils, keeping the grass growing greener longer into the Spring.. There are also proven, significant benefits to the composting process by adding biochar, including a reduction in GHG emissions and speeding up the composting process. That’s one of the reasons that we received a grant from CAL FIRE for a pyrolysis machine, which will hopefully be located at the Napa Recycling and Compost Facility in American Canyon once we get through the permitting process. This location is well situated to be able to supply the vineyards in Napa and Sonoma counties.

This technology is kind of expensive right now but it will get cheaper. We’re still early on in the whole biochar industry. It’s really only been a thing since about 2008 so we’ve actually made a lot of progress in that time. When I started looking into biochar in 2009, nobody had even heard of it. Now most people in agriculture have heard of it. They may not use it, yet, but they are interested in finding out more about it.

Is there anything else you would like our audience to know about how they can participate in the biochar movement?

For every pound of biochar that’s put in the soil, about 2.5 pounds of CO2 is prevented from re-entering the atmosphere. So using biochar in your garden or landscaping is something simple that you can do, as an individual, to address climate change. If everyone in Sonoma Valley did that we could see healthier soils and provide more water retention, and everyone would be contributing in their own small way to draw down carbon from the atmosphere. We need to reduce the amount we’re producing, but we also need to significantly draw down carbon, and biochar provides this as well as multiple other benefits.

In Sonoma County, we have a lot of surplus woody material produced in fuels reduction and fire prevention projects that nobody knows what to do with. If we pyrolyze some of these materials and turn it into biochar, we could make enough to return back into the vineyards, urban landscaping, and grazing lands, which could then save water and improve areas that are not as productive. Water use in Sonoma County and elsewhere in California has become a pretty hot topic and however we can reduce water use and increase water efficiency will become increasingly important.

Lastly, SEC is involved in a pilot study funded by the North Coast Resource Partnership to try to figure out how to aggregate and utilize the locally produced, low-value surplus biomass in one or more biomass “campuses.” This would enable a steady stream of feedstock that could be used by entrepreneurs to make biochar, furniture, construction products, or even to produce renewable energy.